i.

They meet in the summer camp where they are told there’s still time to return to the path to righteousness again, the girl with the knitting needles and the farm girl with the green rain boots. They giggle and listen to each other instead of to the Bible verses about becoming good wives someday to faceless men neither of them want. The instructor tells the girls to be quiet. They ignore her—always a her—because they see the other girls just like them sent here as punishment, and they understand they are not alone. After prayers, the farm girl asks the girl who smuggled in red yarn and knitting needles whether she can make socks for her. Needle girl says she will make the finest socks and finds a tape measure. At her light touch, the farm girl forgets every verse.

ii.

The morning their parents return to drive them back on cornfield-lined roads to homes that are not their homes, the farm girl pulls her boots back on for the mud-slick gravel paths to the parking lot. Before her parents’ truck pulls in and they ask if she’s ready to be a good girl again, needle girl gives her a hat of red yarn, a perfect fit on her head and soft like her cheek against farm girl’s calluses. The two of them promise to stay in contact. But this is how it goes: one email a week becomes one email a month, then two months, then half a year. Needle girl’s family moves to somewhere called the mainland, a land where every word has one of four tones and good girls are called guai yet the word for the strange or the off-kilter is guai with a different tone. Needle girl promises she will return for college, a fancy school with ivy crawling up red bricks that is as far away for the farm girl as the moon.

iii.

Once a year, the woman who was once a girl from a farm flies. She packs a red hat in her fraying suitcase and flies to a town by the sea, Boeing 737 soaring like a metal albatross. Always on July 7th, because she only has enough paid time off to extend her July 4 holiday each year and still have enough days left to visit her parents over the holidays. Every year is the same: farm girl hopes and hopes—they talk and talk over coffee and dinner, shoulders close enough to brush—then needle girl never makes a move. This year needle girl vents about a breakup, a failed relationship with a woman farm girl knows only as a pretty face in the magazines. Needle girl is a somebody, someone who clothes the powerful. Farm girl is a nobody, a nameless paralegal in a nameless law firm in a nameless small town surrounded by cornfields who sends most of her paycheck to keep her parents’ farm afloat amidst crashing crop prices and drought.

Farm girl promises herself this will be the last time. Yet she cannot bring herself to say so, and after needle girl kisses her goodbye and the scent of fake roses lingers on her cheek, she clutches the red hat to her chest at the airport gate, calculating how much to budget for next year’s trip.

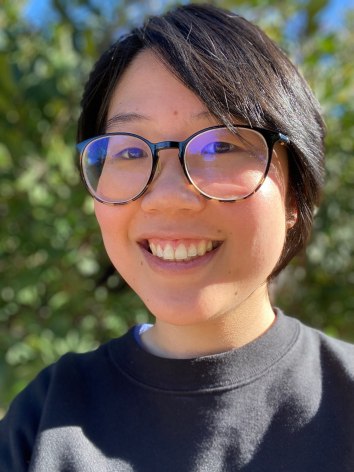

Tina S. Zhu is a Chinese American writer who lives in California. When she’s not writing prose, she sometimes also writes code. Her words have appeared in Pidgeonholes, X-R-A-Y, and Tor.com, among others. Find her on Twitter @tinaszhu or at tinaszhu.com.